Last winter, I spent a month processing our new Harrington College of Design special collection. These books belonged to the Harrington College library until 2015, when the college announced it would close. Columbia College Chicago acquired the books, as well as taking on the remaining Harrington students until they could finish their degrees.

Originally called the Frances Harrington Institution of Interior Decoration, Harrington College was founded in 1931 by Frances Harrington, a New York interior designer. At the time, Chicago was gearing up for the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition, which put the city in an international spotlight and drew in designers. Harrington had lectured in Chicago before, and the college’s curriculum was based on her design lecture series. The books that make up the special collection I processed cover topics that were a part of the school since its early days, mostly architecture, interior design, and fine arts.

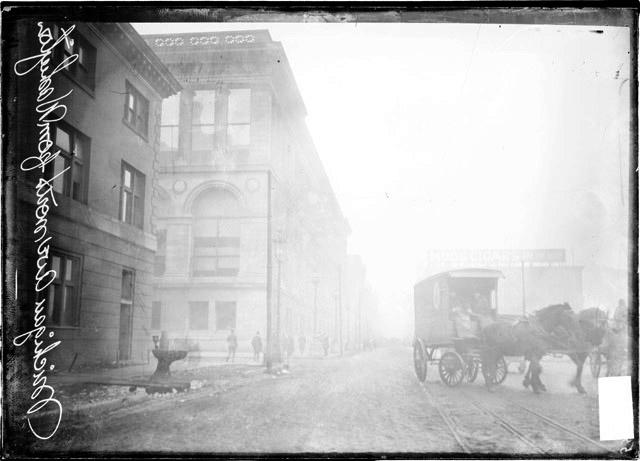

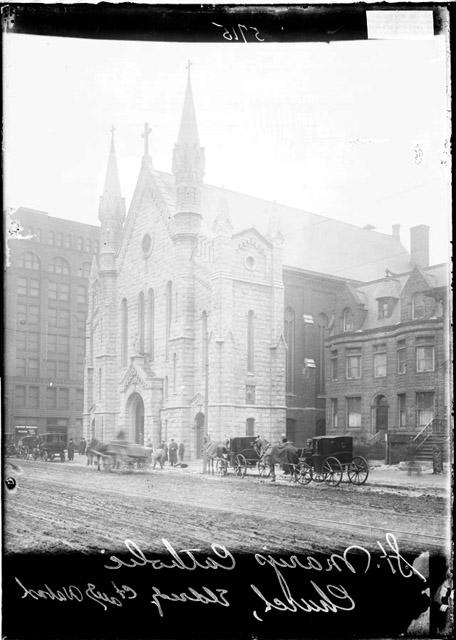

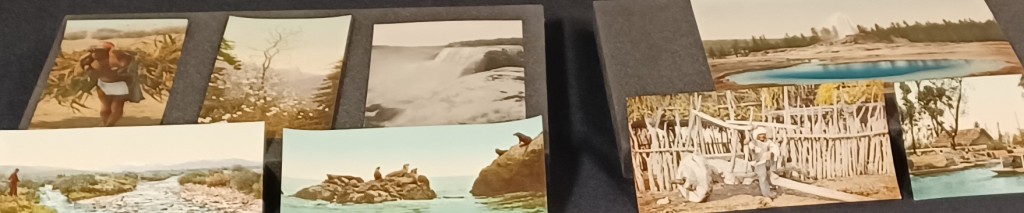

Alder & Sullivan’s Auditorium building, from “Auditorium” by Edward R. Garczynski

Of all the artistic mediums, architecture particularly interests me as an art form that reflects the personality of the artist as well as the state of the society. It’s a medium that the architect Louis H. Sullivan once called, “a beautiful, a sane, a logical, a human, living art.” You could consider architecture a time capsule of different time periods, which might make it seem stuffy or obsolete, since the problems and needs addressed in the designing of a building rarely stick around as the decades stretch on. But if there’s one way to make the past feel exciting, it’s spending hours pouring over books about the whys and wherefores of architectural design.

One of the books in the Harrington collection, Chicago: The World’s Youngest Great City, contains an essay by architect Benjamin H. Marshall that begins, “Chicago has become not only the most interesting city in the United States, but that it is fast becoming one of the most beautiful cities in the world.” This book was published in 1929, when America was on the precipice of the Great Depression but hadn’t yet fallen over the cliff. Chicago was gearing up for the 1933 Century of Progress World’s Fair, which was to be a celebration of the city’s centennial, and the essays in The World’s Youngest Great City feel breathlessly excited to show off what Marshall refers to as a “mushroom growth” of artistic and architectural achievement that blossomed in Chicago in the early 20th century.

That blossoming of innovation was due in large part to the work of three architects who defined a new era of American architecture by rebelling against the past and meeting the demands of the present: H.H. Richardson, Louis H. Sullivan, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

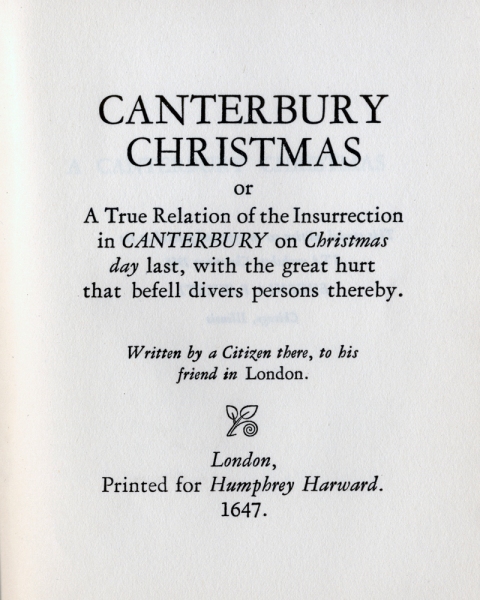

In a book called Three American Architects: Richardson, Sullivan, and Wright, 1865-1915, (not a part of the Harrington collection, but available online) James F. O’Gorman points to the Auditorium building, which Sullivan built with Dankmar Adler in 1889, as the building that marked the height of Chicago’s rebirth after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. At the time, Chicago was in the middle of what Marshall called the “Reign of Terror,” the American adaptation of Victorian style. Hugh Morrison, an architecture professor and biographer of Louis Sullivan, called it “the besetting architectural sin of the nineteenth century,” referring to the fact that the contemporary style was rooted in imitating and blending historical styles such as European Gothic and classical Greek. The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, for which Columbia College Chicago is named, codified this style.

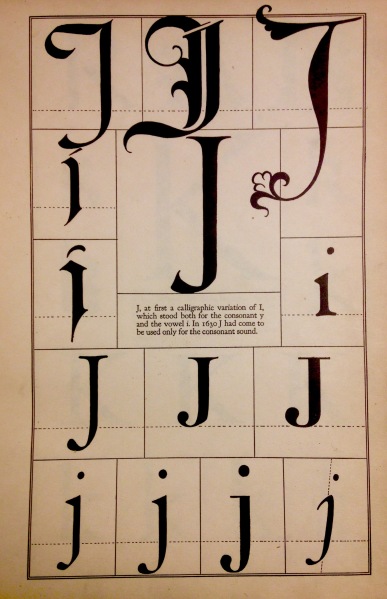

Alder & Sullivan’s Auditorium and what is now Grant Park, from “Auditorium” by Edward R. Garczynski

Louis Sullivan’s rejection of that old-school style of architecture can be seen in the building Adler & Sullivan designed for the Columbian Exposition, the Transportation Building. In a fairground nicknamed the “White City,” the Transportation Building was brightly colored and featured a giant golden archway as an entrance. In his 1935 biography of Sullivan, Hugh Morrison wrote, “if the White City was a dream of beauty, it was a dangerous and spurious kind of beauty, spurious because it appropriated the forms of a culture not its own, dangerous because it seemed to do this so successfully. It represented the acme of all that Sullivan had fought against during his whole life.”

Much of Sullivan’s personal style was inspired by H.H. Richardson, an architect who, according to O’Gorman, helped define the two separate social spheres that emerged in American culture after the Civil War: “the urban commercial block and the suburban single-family house.” Sullivan, particularly inspired by the ornamentation of Richardson’s Marshall Field Wholesale Store, would go on to gain recognition for his commercial buildings, while his protege, Frank Lloyd Wright, is most often recognized for his private homes. Philip Johnson, another architect, damned Sullivan with faint praise in an essay by calling him “the second-best Richardsonian architect in the city in the great period of Chicago architecture.”

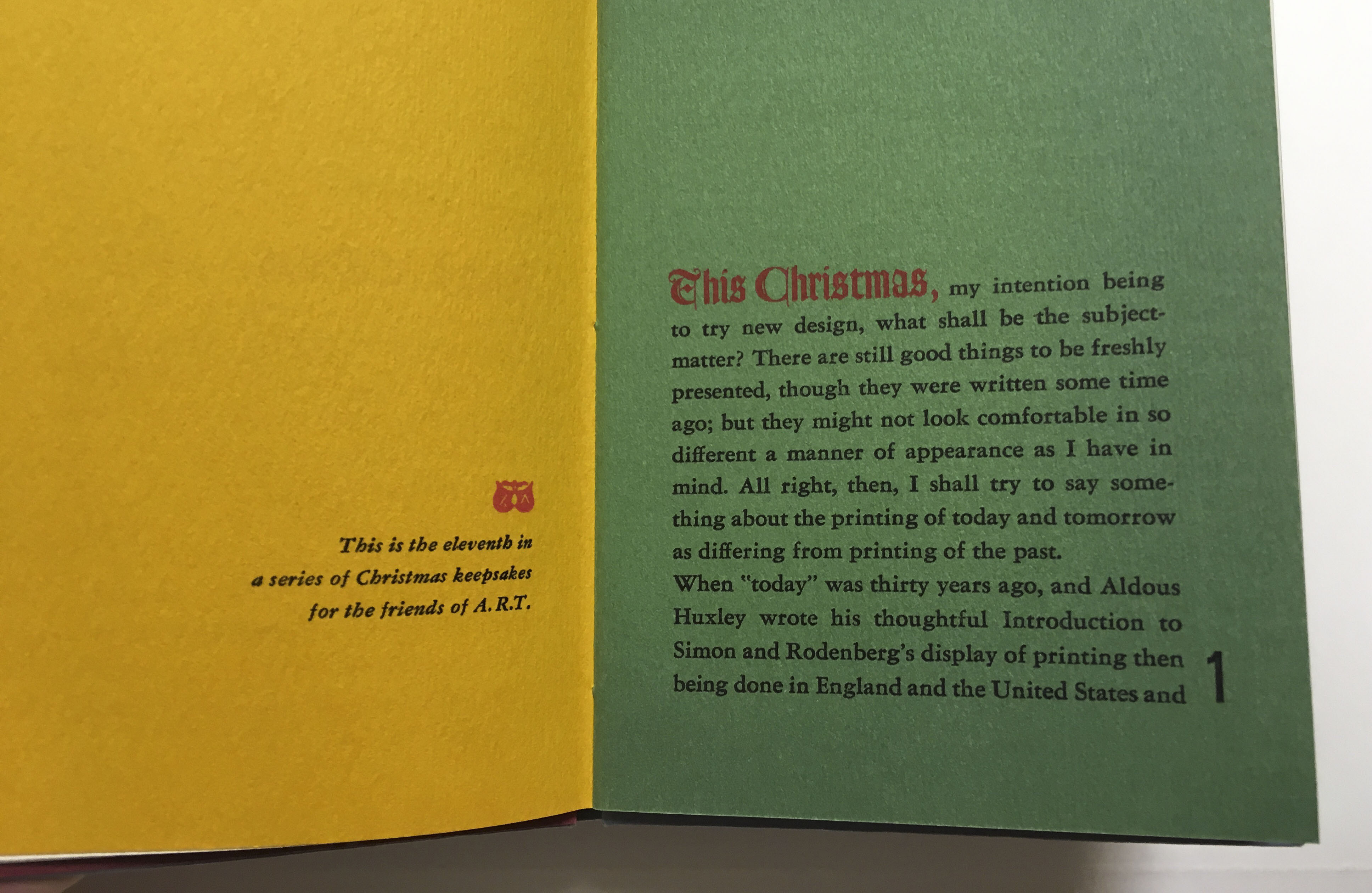

It was the mixed-use Auditorium building that first won the firm of Adler & Sullivan widespread recognition, and the influence of H.H. Richardson can clearly be seen in its design. In a commemorative book about the Auditorium first published in 1890, Edward R. Garczynski called the building, “Chicago to the smallest detail.” The design was rooted in Chicago tradition, and special attention was paid to choosing materials that would be fire-proof, as the city was still wary of the possibility of another Great Fire.

One of the draftsmen who worked on the Auditorium project, Frank Lloyd Wright, found a comfortable niche at the Adler & Sullivan firm working on all the commissions for private residences that Louis Sullivan didn’t have an interest in. The enmeshing of nature and construction that became a staple of the “Prairie School” architectural style founded by Wright nevertheless owes a lot to Sullivan, who found a lot of inspiration in books such as Gray’s Manual of Botany and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Wright was trained as an engineer and in aesthetic theory, so everything he knew about the actual practice of architecture came from his time at Adler & Sullivan.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s style would eventually help define a period of architecture known as International architecture, which, like its name implies, expanded the influence of Chicago architecture to the rest of the world. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a German architect, was inspired by Wright’s style during the process of designing a house for Dr. Edith Farnsworth in Plano, Illinois. If Wright’s Prairie houses intended to blend the natural with the man-made, Mies went a step farther by building the Farnsworth house as a single large room with glass walls. The Farnsworth House by Franz Schulze quotes an unnamed guest who stayed at the house: “You are in nature and not in it, engulfed by it but separate from it. It is altogether unforgettable.”

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, from “The Farnsworth House” by Franz Schulze

Though Mies was not the first architect to build a house of glass, Philip Johnson, who completed his three years earlier in 1949, acknowledged that his Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, was inspired by Mies’ early designs for the Farnsworth House. Johnson was influenced by Mies in much the same way that Frank Lloyd Wright was influenced by Louis Sullivan, and architecture historian Vincent Scully said that one of Johnson’s accomplishments was that he “revived the great literate tradition of Sullivan and Wright” after their philosophy of romantic individualism fell out of style at the end of the 19th century.

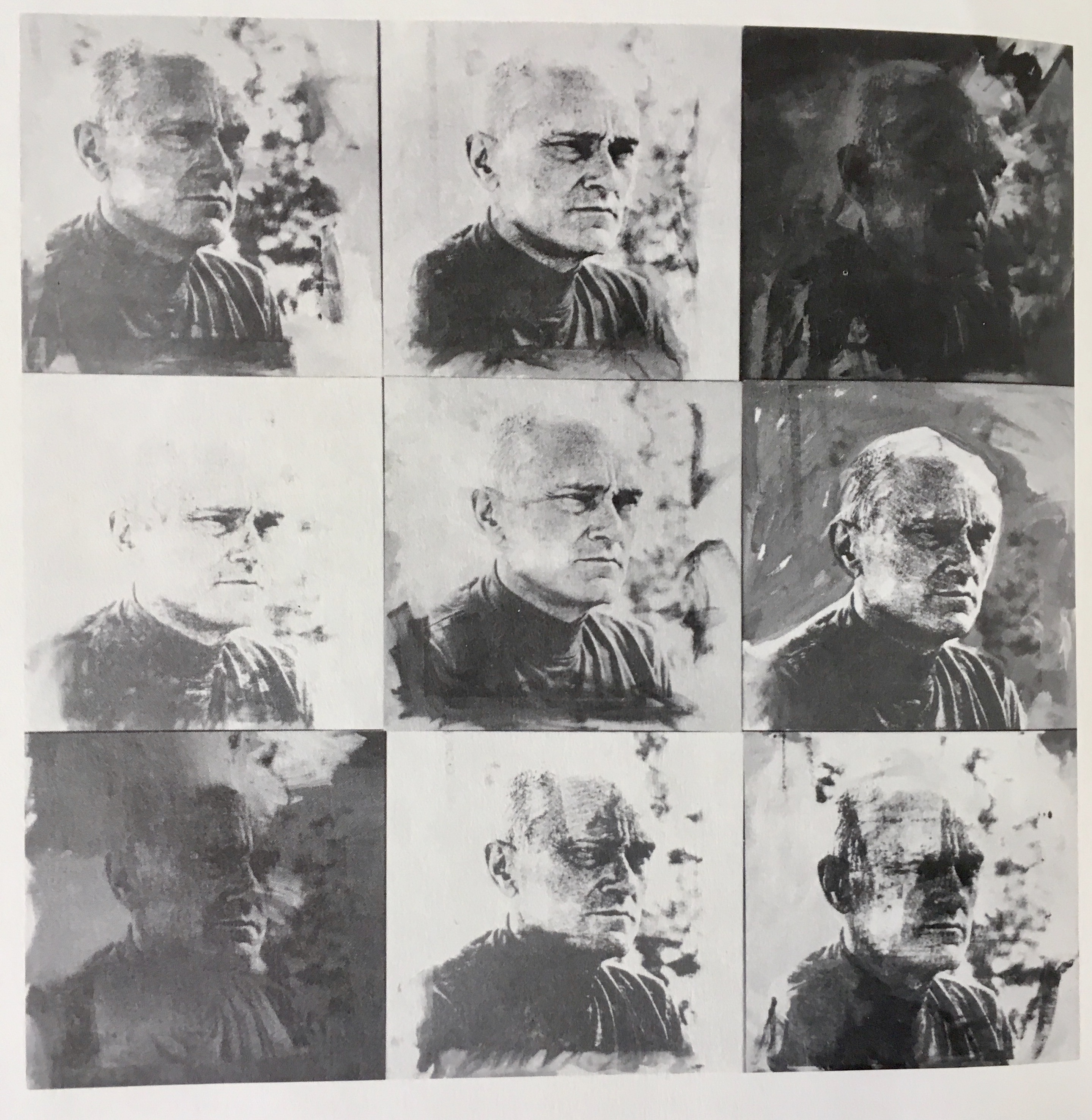

Philip Johnson by Andy Warhol, from “Writings” by Philip Johnson

Johnson is famous for his postmodern buildings, like his skyscraper at 550 Madison Avenue, which brings us back to the place we started. Postmodernist architecture often borrows elements from other, older styles. Though the two are ideologically disparate, the postmodern architecture of the 20th century is just as eclectic as the mishmash of styles used in the 1893 Columbian Exposition and in architecture at large in the 19th century. Frustrated at other architects’ habit of copying historical styles without considering the purpose of the building, Louis Sullivan once wrote, “I urge you to cast away as worthless the shop-worn and empirical notion that an architect is an artist–and accept my assurance that he is and imperatively shall be an interpreter of the national life of his time. If you realize this, you will realize at once and forever that you…are called upon, not to betray, but to express the life of your own day and generation,” a sentiment that is as valuable to architecture as it is to every discipline.

Below, you’ll see a map of all the buildings I mentioned (plus a few bonus buildings), and below that, the list of books I used for research, almost all of which came from the Harrington collection. By no definition is this an exhaustive history of Chicago architecture and architects. I didn’t even touch on the Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill firm, who built the Sears Tower and helped save the Adler & Sullivan Stock Exchange trading floor from demolition, or on John Root, who Philip Johnson said was the best Richardsonian architect in Chicago, ahead of Louis Sullivan. To get a sense of the vast scope of Chicago architects and their relationships over the last couple of centuries, check out the Chicago Architects Project by the Society of Architectural Historians or the Chicago Architecture Foundation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barr, Alfred H., Jr. Modern Architects. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1932.

Butler, Rush C. Chicago: The World’s Youngest Great City. Miehle Printing Press & MFG Co., 1929.

Chapman, Linda L., David C. Huntley, and Joyce Jackson. Louis H. Sullivan Architectural Ornaments. Office of Cultural Arts and University Museums, Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, 1981.

Garczynski, Edward R. Auditorium. The Prairie Avenue Bookshop, 2007.

Johnson, Philip. Writings. Oxford University Press, 1979.

Lefkowitz, Helen. “The First Forty Years.” Chicago History: The Magazine of the Chicago Historical Society. Spring 1979.

Morrison, Hugh. Louis Sullivan: Prophet of Modern Architecture. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1935.

Schulze, Franz. The Farnsworth House. Lohan Associates, 1997.

Vinci, John. The Art Institute of Chicago: The Stock Exchange Trading Room. The Art Institute of Chicago, 1977.

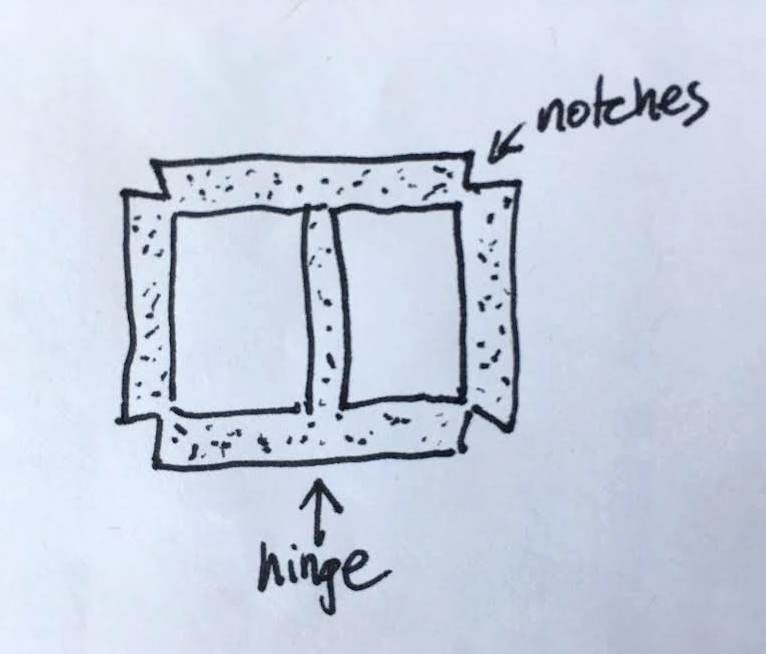

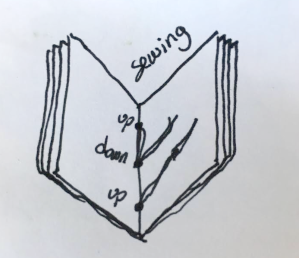

The days are getting shorter, the nights are getting colder, and that means we’re getting closer and closer to the biggest gift-giving holidays of the year. I’ve never been great at giving gifts. If I stumble on something that one of my friends or family members will love, I feel secure in my gift-giving abilities, but often I’m at a loss for ideas, since I always want my presents to be perfect and unique. If you’re really dedicated to upping your gift-giving game, though, you could try making gifts yourself.

The days are getting shorter, the nights are getting colder, and that means we’re getting closer and closer to the biggest gift-giving holidays of the year. I’ve never been great at giving gifts. If I stumble on something that one of my friends or family members will love, I feel secure in my gift-giving abilities, but often I’m at a loss for ideas, since I always want my presents to be perfect and unique. If you’re really dedicated to upping your gift-giving game, though, you could try making gifts yourself.